|

Few writers are ever fortunate enough to number their books in the hundreds, but Black Horse Western writer Leonard F Meares was one of them. When he died in 1993, Len could lay claim to more than 700 published novels -- 746, to be precise -- the overwhelming majority of which were westerns.

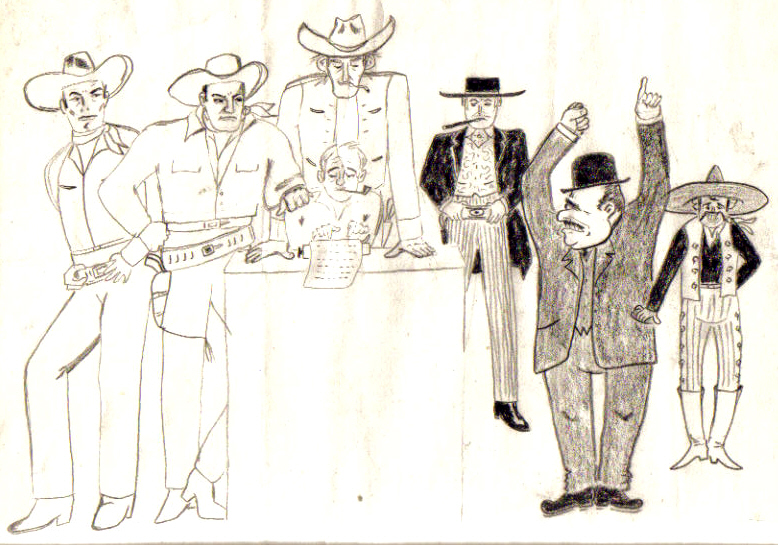

Leonard Frank Meares was best known to western fans the world over as "Marshall Grover", creator of Texas trouble-shooters Larry and Stretch. He was born in Sydney, Australia, on 13 February 1921, and started reading the westerns of Zane Grey, Clarence E Mulford and William Colt MacDonald when he was still a child. A lifelong movie buff with a particular fondness for shoot-'em-ups, he later recalled, "At that early age I got a kick out of the humorous patches often seen in Buck Jones films, and realised that humour should always be an integral part of any western."

Len worked at a variety of jobs after leaving school, including shoe salesman, and during the Second World War he served with the Royal Australian Air Force. When he returned to civilian life in 1946, he went to work at Australia's Department of Immigration.

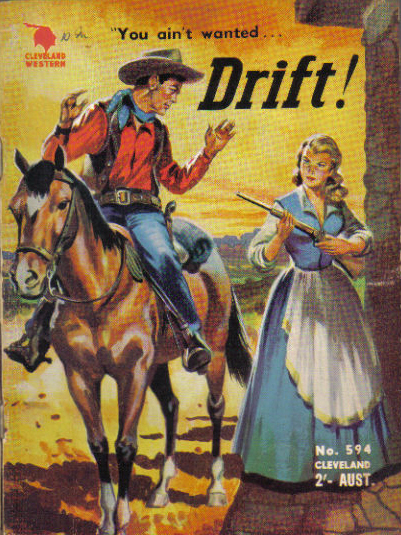

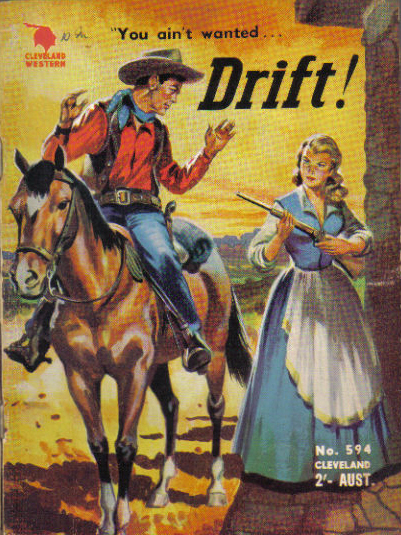

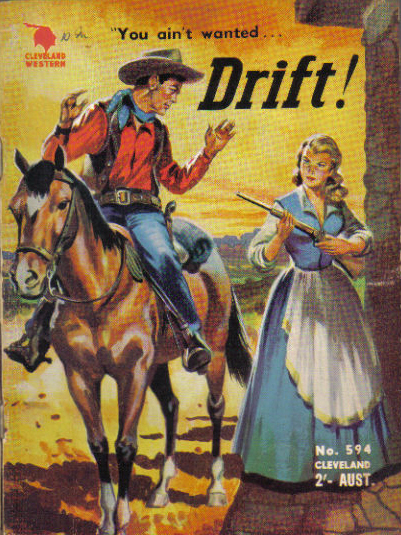

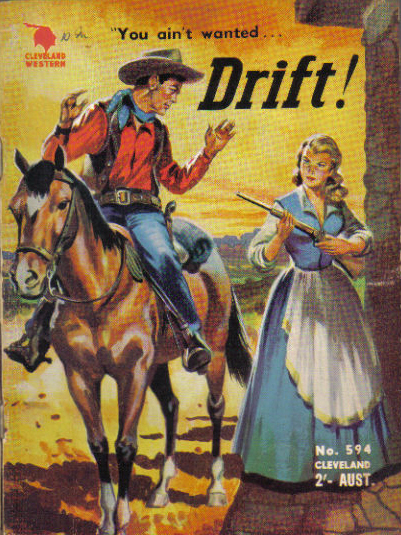

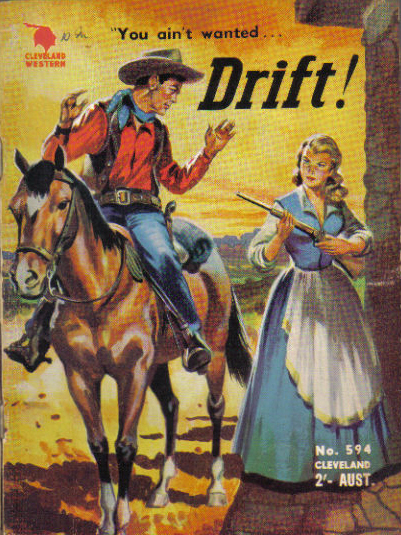

The aspiring author bought his first typewriter in the mid-1950s with the intention of writing for radio and the cinema, but when this proved to be easier said than done, he decided to try his hand at popular fiction instead. Since a great many paperback westerns were being published locally, he set about writing one of his own. The result, Trouble Town, was published by the Cleveland Publishing Company in 1955. Although Len had devised the pseudonym "Marshall Grover" for his first book, however, Cleveland decided to issue it under the name Johnny Nelson. "I'm still chagrined about that," he told me years later. Undaunted, he quickly developed a facility for writing westerns, and Cleveland eventually put him under contract. His tenth yarn, Drift!, (1956), introduced his fiddle-footed knights-errant, Larry Valentine and Stretch Emerson, the characters for which he would eventually become so beloved. And nowhere was the author's quirky sense of humor more apparent than in these action-packed and always painstakingly plotted yarns.

With his work appearing under such names as "Ward Brennan", "Glenn Murrell", "Shad Denver" and even "Brett Waring" (a pseudonym more correctly associated with Keith Hetherington), Len never needed more than 24 hours to devise a new plot. "Irving Berlin once said that there are so many notes on a keyboard from which to create a new melody, and it's the same with writing on a treadmill basis."

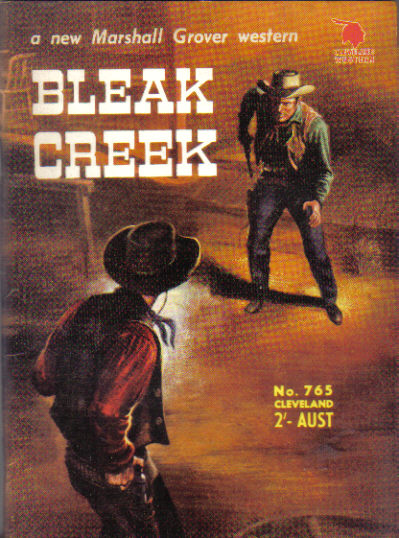

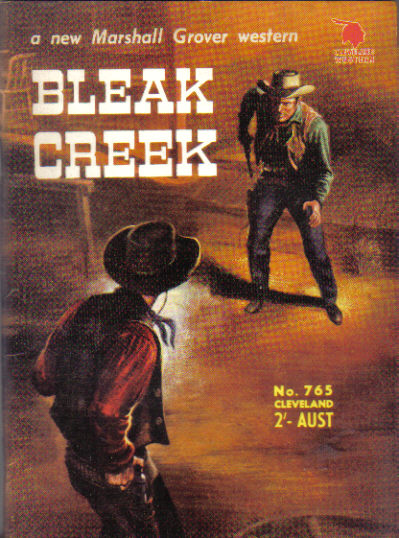

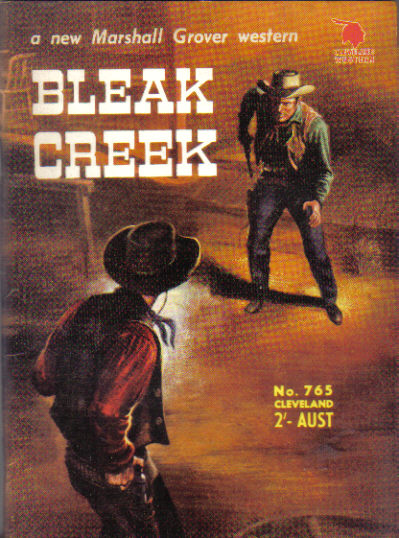

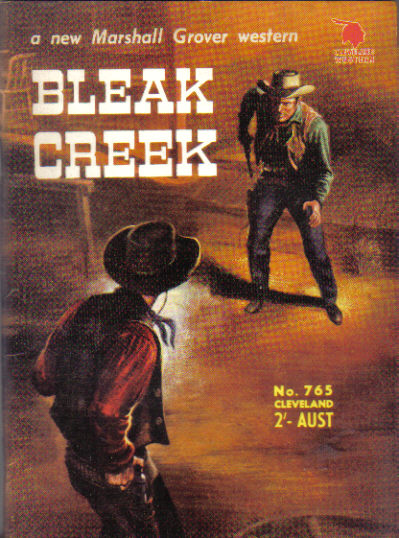

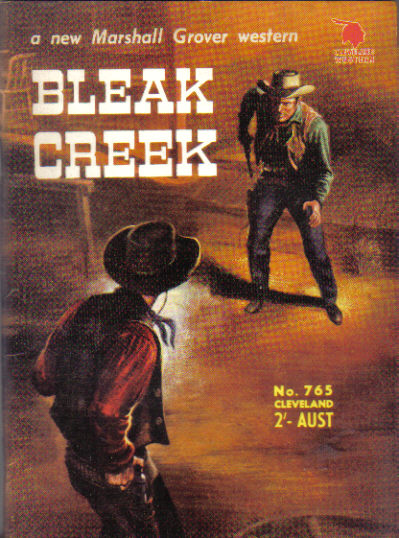

At his most prolific, the by-now full-time writer could turn out around thirty books a year. In 1960, he created a brief but memorable series of westerns set in and around the town of Bleak Creek. Four years later came The Night McLennan Died, the first of more than 70 oaters to feature cavalryman-turned-manhunter Big Jim Rand.

In mid-1966, Len left Cleveland and started writing exclusively for the Horwitz Group. Quick to exploit its latest asset, Horwitz soon sold more than 30 novels to Bantam Books for publication in the United States, where for legal reasons "Marshall Grover" became "Marshall McCoy", "Larry and Stretch" became "Larry and Streak" and "Big Jim Rand" became "Nevada Jim Gage". With their tighter editing and wonderful James Bama covers, I believe the westerns issued during this period are probably the author's best.

Although I started reading the Larry and Stretch series when I was about 10 years old, it wasn't until 1979 (and I had reached the ripe old age of 21) that I finally decided to contact the author, via his publisher. When he eventually replied, I discovered a genial, self-deprecating and incredibly genuine man who showed real interest in his readers. And since we seemed to hit it off so well, what started out as a simple, one-off letter of appreciation quickly blossomed into a warm and lively correspondence which was to last for 14 years.

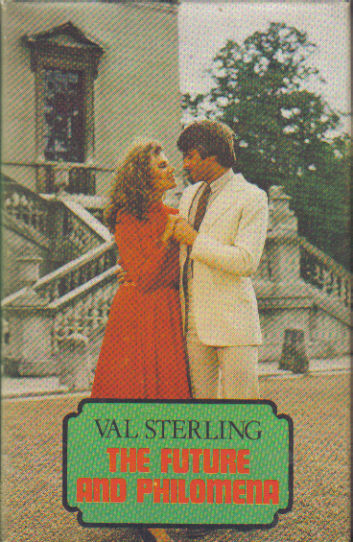

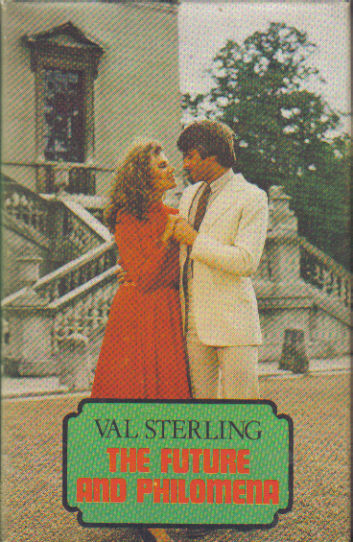

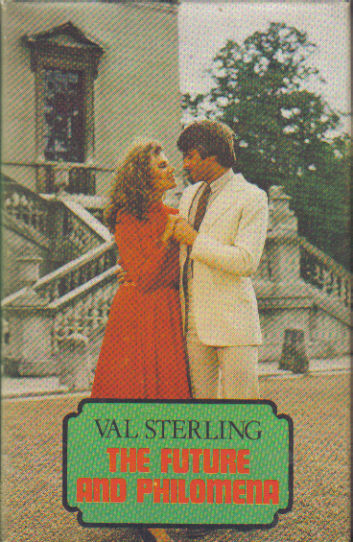

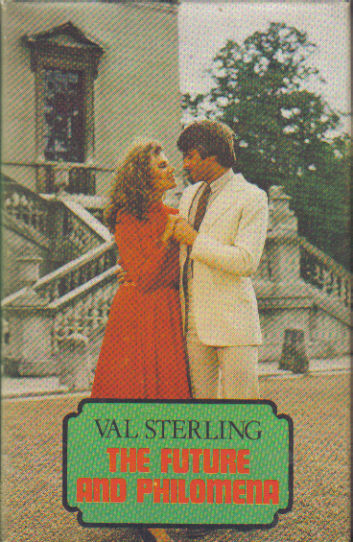

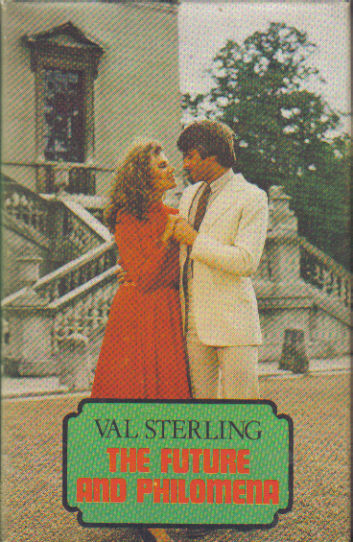

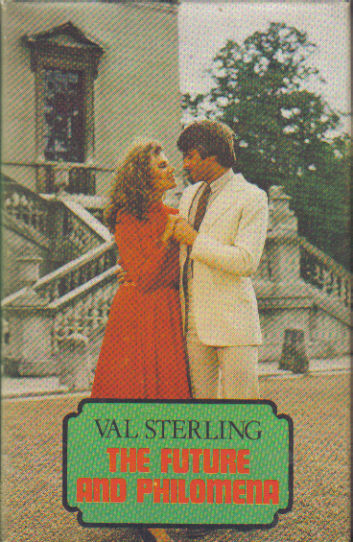

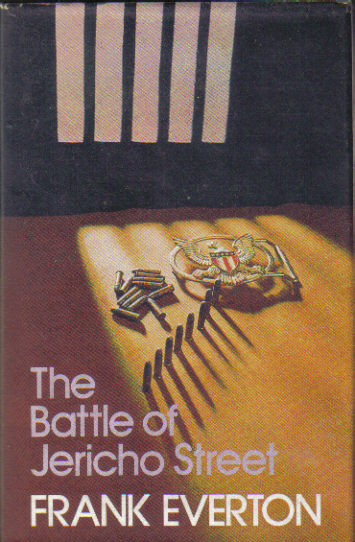

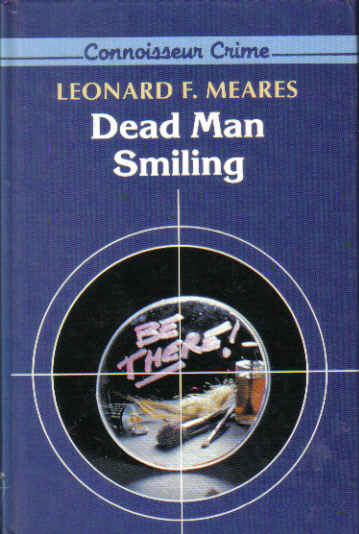

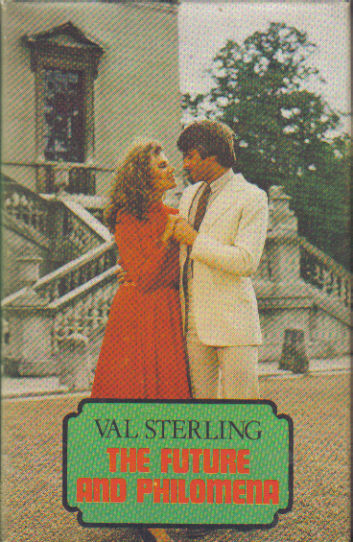

Len began his association with Robert Hale Limited in 1981, with Jo Jo and the Private Eye, the first of five "Marty Moon" detective novels published under the name "Lester Malloy". Hale also issued his offbeat romance, The Future and Philomena, as by "Val Sterling", in 1982. He even scored with two stand-alone crime novels, The Battle of Jericho Street (1984) as by "Frank Everton", and Dead Man Smiling (1986), published under his own name.

His first Black Horse Western was, fittingly enough, a Larry and Stretch yarn entitled Rescue a Tall Texan (1989). It's an entertaining entry in the long-running series in which Stretch, the homely, amiable but always slower-witted half of the duo, is kidnapped by an outlaw gang in need of a hostage. Naturally, Larry quickly sets out to track down and rescue his partner, and is joined along the way by an erudite half-Sioux Indian with the unlikely name of Cathcart P. Slow Wolf, and the always-apoplectic Pinkerton operative, Dan Hoolihan, both popular recurring characters in the series. The climax is a typically robust shootout in which Larry and Stretch mix it up with no less than 13 hardcases -- 13, in this instance, proving to be an extremely unlucky number for the bad guys.

At Len's suggestion, the UK hardcover rights in Rescue a Tall Texan were sold to Hale by the Horwitz Group, and I've always wondered why Horwitz never tried to sell any further Larry and Stretch westerns on to the good folks at Clerkenwell House. Certainly, these books remain enormously popular with the library readership, and Ulverscroft continue to issue large print Linford editions, even today.

In any case, Len soon decided to create a new double-act specifically for the Black Horse Western market, in the shape of husband-and-wife detectives Rick and Hattie Braddock.

Rick and Hattie first appeared in Colorado Runaround, which was published in 1991. Rick is a former cowboy, actor and gambler, Hattie (nee Keever) a one-time magician's assistant, chorus girl and knife-thrower's target. Thrown together by circumstances, the couple eventually fall in love, get spliced and set up the Braddock Detective Agency. Their first case involves the disappearance of a wealthy rancher's daughter, and it takes place -- as did all of Len's westerns -- on an historically sketchy but always largely good-natured frontier, where the harsh realities of life seldom make an appearance.

And in that last respect, Len's fiction always reflected his own character, for here was a very moral and fair-minded man with a commendably innocent, straightforward and almost naive outlook on life -- a man who would always rather see the good in a person, place or situation than the bad.

Colorado Runaround, like the BHWs which followed it, is typical -- though not vintage -- Meares. There's a deceptively intricate plot, regular bursts of action, oddball supporting characters and plenty of laughs. In all respects, it is the work of a writer's writer. But the humour is somewhat hit-or-miss, and is as likely to make the story as break it.

This observation also applies to Len's three "Rick and Hattie" sequels, The Major and the Miners (1992), in which the heroes attempt to solve a whole passel of mysteries and restore peace to an increasingly restive mining town; Five Deadly Shadows (1993), a far more satisfying kidnap story; and Feud at Greco Canyon (1994), in which the happily married sleuths work overtime to avert a full-scale range-war.

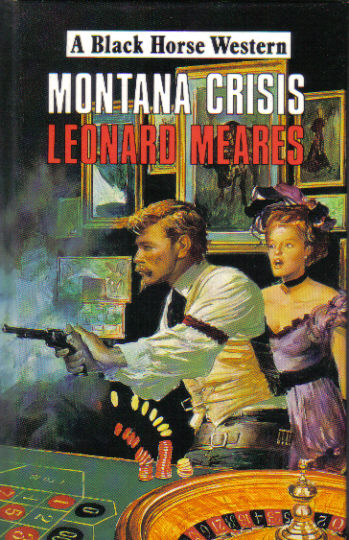

Len's final western series, set in Rampart County, Montana, is probably his most disappointing. Montana Crisis (1993) is a pretty standard tale about how a growing town gets a sheriff -- in the form of overly officious ex-Pinkerton operative Francis X. Rooney -- and his laconic deputy, Memphis Beck. In the first adventure, they break the iron rule of megalomaniac entrepreneur Leon Coghill, but curiously, there's more talk than action.

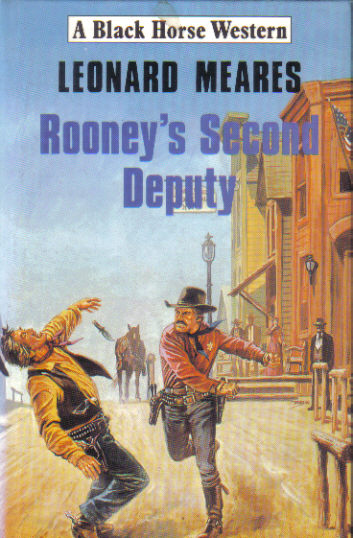

Things perk up a bit in the sequel, Rooney's Second Deputy (1994), a mystery that also involves a daring robbery. This time round, the story is propelled more by gambler Beau Latimore (the deputy of the title) and Len's supporting characters, who prove to be far more "reader friendly" than the starchy Rooney.

In summary then, it is probably fairer to judge Len's undoubted merits as a western writer more on his Cleveland and Horwitz titles -- which I cannot praise highly enough -- than those he wrote for Hale. But why should this be?

To answer that question, we need to understand what was happening in Len's professional life at that time they were written.

In the spring of 1991, the author was requested by Horwitz not to produce any more Larry and Stretch westerns for six months. Apparently, Horwitz had built up a substantial backlog of material, and couldn't see much point in buying new manuscripts when there were so many older ones still awaiting publication. It was during this period that Len wrote and sold his first BHW.

When he delivered his next "Marshall Grover" book ahead of Christmas 1991, however, Horwitz dropped a bombshell. The company had decided to close down its paperback arm altogether, and in future would only require one Larry and Stretch story each month (as against the two Len usually produced), to sell on to the still-buoyant Scandinavian market.

Len's wife, Vida, put it this way: "He was more or less sacked."

Len's immediate instinct was to find another publisher and continue writing Marshall Grover westerns for the English-speaking market. Under the terms of his contract, however, Horwitz owned both the Grover name and the Grover characters -- and weren't about to allow him to take them anywhere else.

To a man who had spent 36 years as "the Marshall", and almost as long writing literally hundreds of Larry and Stretch yarns, it was a devastating turn of events -- not least financially -- and Len quickly went into decline. In a letter to me, Vida Meares remembered, "When out of our home or talking on the phone, [Len] was still the same cheerful, quick-witted man, but at home he was downhearted and feeling well-nigh finished."

And though he continued to write Larry and Stretch, he often told me how unhappy he was that his English-speaking fans, who had stuck with the series for so long, would no longer get the chance to follow the Texans' adventures.

This, then, was the backdrop against which Len wrote his Black Horse Westerns. In low spirits, and with his professional life in turmoil, I believe he was attempting to create new characters to replace those who had become his constant companions over the years, and whom he viewed very much as his "children". But though he gave each and every one of his BHWs as much care and attention as possible, Larry and Stretch proved to be an impossible act to follow -- which only depressed him more.

Just over a year later, in January 1993, Len contracted viral pneumonia and was hospitalised for the condition. His daughter Gaby later wrote to me, "When I visited him on 3 February, he was giving the nurses cheek and, as usual, more concerned about my mother's welfare than his own." Early the following morning, however, he took a sudden turn for the worse and passed away in his sleep.

Vida Meares told me, "Marshall Grover and my husband were the same person -- and Horwitz killed Marshall Grover."

Though this was clearly not the case, I do believe that the decision taken by Horwitz to stop publishing Larry and Stretch, coupled with their refusal to allow him to take his pseudonym and characters elsewhere, certainly contributed to Len's decline.

The last two Leonard Meares books to appear in the BHW line -- Tin Star Trio (1994) and A Quest of Heroes (1996) -- were written not by Len at all, but by Link Hullar (himself the author of five BHWs) and me, from fragments found among Len's papers.

Tin Star Trio began life as an untitled short story featuring two drifters called Zack Holley and Curly Ryker. As soon as I started reading it, I realised that Len had been toying with the idea of continuing to write Larry and Stretch -- most probably for publication by Hale -- but changing the characters' names to avoid any legal difficulties. The story revolved around a missing cashbox hidden in a remote canyon, and told how Zack and Curly manage to thwart the attempts of a band of outlaws to retrieve it.

Link and I both felt that it would be a nice to expand the story into a short novel, and with the blessing of Vida Meares, that's exactly what we did. Although we aged the characters a little (because we've both always preferred westerns that feature older, slightly over-the-hill heroes), we tried to recapture some of the spirit of Len at his best. Even the titles of the chapters are all taken from previous Larry and Stretch books.

A Quest of Heroes came about at the suggestion of Australian singer Dave Mathewson, a Marshall Grover fan from way back, who had earlier recorded a sort of "tribute album" entitled The Marshall, Larry and Stretch and Me and You. Dave's brief plot, which was all about a bandit gang who kidnap white women in order to sell them into slavery south of the border, gave us an ideal opportunity to bring back not just Larry and Stretch (here once again masquerading as Zack and Curly), but all of Len's best-known characters, including Big Jim Rand, Slow Wolf, Dan Hoolihan and more. Naturally, we had to change the names of all the main players, but I like to think that we produced a book that Len would have approved of.

In any case, it's hardly my place to pass judgement on either Tin Star Trio or A Quest of Heroes, but I must say that I could not have wished for a better collaborator on these two projects. Link Hullar, like myself, was a close friend and fan of Len's, and I have always considered Link to be Len's natural successor.

Even though the BHWs of Len Meares might not be among his greatest achievements, I still enjoy re-reading them occasionally. Be they good, bad or indifferent, Len himself is there in every line, and reading them again is like visiting with him again. He was a skilled and tireless writer, a truly wonderful friend, and I remember him -- will always remember him -- with tremendous affection.

This article first appeared in the pages of Keith Chapman's Black Horse Extra. www.blackhorsewesterns.com

Leonard Frank Meares was best known to western fans the world over as "Marshall Grover", creator of Texas trouble-shooters Larry and Stretch. He was born in Sydney, Australia, on 13 February 1921, and started reading the westerns of Zane Grey, Clarence E Mulford and William Colt MacDonald when he was still a child. A lifelong movie buff with a particular fondness for shoot-'em-ups, he later recalled, "At that early age I got a kick out of the humorous patches often seen in Buck Jones films, and realised that humour should always be an integral part of any western."

Len worked at a variety of jobs after leaving school, including shoe salesman, and during the Second World War he served with the Royal Australian Air Force. When he returned to civilian life in 1946, he went to work at Australia's Department of Immigration.

The aspiring author bought his first typewriter in the mid-1950s with the intention of writing for radio and the cinema, but when this proved to be easier said than done, he decided to try his hand at popular fiction instead. Since a great many paperback westerns were being published locally, he set about writing one of his own. The result, Trouble Town, was published by the Cleveland Publishing Company in 1955. Although Len had devised the pseudonym "Marshall Grover" for his first book, however, Cleveland decided to issue it under the name Johnny Nelson. "I'm still chagrined about that," he told me years later. Undaunted, he quickly developed a facility for writing westerns, and Cleveland eventually put him under contract. His tenth yarn, Drift!, (1956), introduced his fiddle-footed knights-errant, Larry Valentine and Stretch Emerson, the characters for which he would eventually become so beloved. And nowhere was the author's quirky sense of humor more apparent than in these action-packed and always painstakingly plotted yarns.

With his work appearing under such names as "Ward Brennan", "Glenn Murrell", "Shad Denver" and even "Brett Waring" (a pseudonym more correctly associated with Keith Hetherington), Len never needed more than 24 hours to devise a new plot. "Irving Berlin once said that there are so many notes on a keyboard from which to create a new melody, and it's the same with writing on a treadmill basis."

At his most prolific, the by-now full-time writer could turn out around thirty books a year. In 1960, he created a brief but memorable series of westerns set in and around the town of Bleak Creek. Four years later came The Night McLennan Died, the first of more than 70 oaters to feature cavalryman-turned-manhunter Big Jim Rand.

In mid-1966, Len left Cleveland and started writing exclusively for the Horwitz Group. Quick to exploit its latest asset, Horwitz soon sold more than 30 novels to Bantam Books for publication in the United States, where for legal reasons "Marshall Grover" became "Marshall McCoy", "Larry and Stretch" became "Larry and Streak" and "Big Jim Rand" became "Nevada Jim Gage". With their tighter editing and wonderful James Bama covers, I believe the westerns issued during this period are probably the author's best.

Although I started reading the Larry and Stretch series when I was about 10 years old, it wasn't until 1979 (and I had reached the ripe old age of 21) that I finally decided to contact the author, via his publisher. When he eventually replied, I discovered a genial, self-deprecating and incredibly genuine man who showed real interest in his readers. And since we seemed to hit it off so well, what started out as a simple, one-off letter of appreciation quickly blossomed into a warm and lively correspondence which was to last for 14 years.

Len began his association with Robert Hale Limited in 1981, with Jo Jo and the Private Eye, the first of five "Marty Moon" detective novels published under the name "Lester Malloy". Hale also issued his offbeat romance, The Future and Philomena, as by "Val Sterling", in 1982. He even scored with two stand-alone crime novels, The Battle of Jericho Street (1984) as by "Frank Everton", and Dead Man Smiling (1986), published under his own name.

His first Black Horse Western was, fittingly enough, a Larry and Stretch yarn entitled Rescue a Tall Texan (1989). It's an entertaining entry in the long-running series in which Stretch, the homely, amiable but always slower-witted half of the duo, is kidnapped by an outlaw gang in need of a hostage. Naturally, Larry quickly sets out to track down and rescue his partner, and is joined along the way by an erudite half-Sioux Indian with the unlikely name of Cathcart P. Slow Wolf, and the always-apoplectic Pinkerton operative, Dan Hoolihan, both popular recurring characters in the series. The climax is a typically robust shootout in which Larry and Stretch mix it up with no less than 13 hardcases -- 13, in this instance, proving to be an extremely unlucky number for the bad guys.

At Len's suggestion, the UK hardcover rights in Rescue a Tall Texan were sold to Hale by the Horwitz Group, and I've always wondered why Horwitz never tried to sell any further Larry and Stretch westerns on to the good folks at Clerkenwell House. Certainly, these books remain enormously popular with the library readership, and Ulverscroft continue to issue large print Linford editions, even today.

In any case, Len soon decided to create a new double-act specifically for the Black Horse Western market, in the shape of husband-and-wife detectives Rick and Hattie Braddock.

Rick and Hattie first appeared in Colorado Runaround, which was published in 1991. Rick is a former cowboy, actor and gambler, Hattie (nee Keever) a one-time magician's assistant, chorus girl and knife-thrower's target. Thrown together by circumstances, the couple eventually fall in love, get spliced and set up the Braddock Detective Agency. Their first case involves the disappearance of a wealthy rancher's daughter, and it takes place -- as did all of Len's westerns -- on an historically sketchy but always largely good-natured frontier, where the harsh realities of life seldom make an appearance.

And in that last respect, Len's fiction always reflected his own character, for here was a very moral and fair-minded man with a commendably innocent, straightforward and almost naive outlook on life -- a man who would always rather see the good in a person, place or situation than the bad.

Colorado Runaround, like the BHWs which followed it, is typical -- though not vintage -- Meares. There's a deceptively intricate plot, regular bursts of action, oddball supporting characters and plenty of laughs. In all respects, it is the work of a writer's writer. But the humour is somewhat hit-or-miss, and is as likely to make the story as break it.

This observation also applies to Len's three "Rick and Hattie" sequels, The Major and the Miners (1992), in which the heroes attempt to solve a whole passel of mysteries and restore peace to an increasingly restive mining town; Five Deadly Shadows (1993), a far more satisfying kidnap story; and Feud at Greco Canyon (1994), in which the happily married sleuths work overtime to avert a full-scale range-war.

Len's final western series, set in Rampart County, Montana, is probably his most disappointing. Montana Crisis (1993) is a pretty standard tale about how a growing town gets a sheriff -- in the form of overly officious ex-Pinkerton operative Francis X. Rooney -- and his laconic deputy, Memphis Beck. In the first adventure, they break the iron rule of megalomaniac entrepreneur Leon Coghill, but curiously, there's more talk than action.

Things perk up a bit in the sequel, Rooney's Second Deputy (1994), a mystery that also involves a daring robbery. This time round, the story is propelled more by gambler Beau Latimore (the deputy of the title) and Len's supporting characters, who prove to be far more "reader friendly" than the starchy Rooney.

In summary then, it is probably fairer to judge Len's undoubted merits as a western writer more on his Cleveland and Horwitz titles -- which I cannot praise highly enough -- than those he wrote for Hale. But why should this be?

To answer that question, we need to understand what was happening in Len's professional life at that time they were written.

In the spring of 1991, the author was requested by Horwitz not to produce any more Larry and Stretch westerns for six months. Apparently, Horwitz had built up a substantial backlog of material, and couldn't see much point in buying new manuscripts when there were so many older ones still awaiting publication. It was during this period that Len wrote and sold his first BHW.

When he delivered his next "Marshall Grover" book ahead of Christmas 1991, however, Horwitz dropped a bombshell. The company had decided to close down its paperback arm altogether, and in future would only require one Larry and Stretch story each month (as against the two Len usually produced), to sell on to the still-buoyant Scandinavian market.

Len's wife, Vida, put it this way: "He was more or less sacked."

Len's immediate instinct was to find another publisher and continue writing Marshall Grover westerns for the English-speaking market. Under the terms of his contract, however, Horwitz owned both the Grover name and the Grover characters -- and weren't about to allow him to take them anywhere else.

To a man who had spent 36 years as "the Marshall", and almost as long writing literally hundreds of Larry and Stretch yarns, it was a devastating turn of events -- not least financially -- and Len quickly went into decline. In a letter to me, Vida Meares remembered, "When out of our home or talking on the phone, [Len] was still the same cheerful, quick-witted man, but at home he was downhearted and feeling well-nigh finished."

And though he continued to write Larry and Stretch, he often told me how unhappy he was that his English-speaking fans, who had stuck with the series for so long, would no longer get the chance to follow the Texans' adventures.

This, then, was the backdrop against which Len wrote his Black Horse Westerns. In low spirits, and with his professional life in turmoil, I believe he was attempting to create new characters to replace those who had become his constant companions over the years, and whom he viewed very much as his "children". But though he gave each and every one of his BHWs as much care and attention as possible, Larry and Stretch proved to be an impossible act to follow -- which only depressed him more.

Just over a year later, in January 1993, Len contracted viral pneumonia and was hospitalised for the condition. His daughter Gaby later wrote to me, "When I visited him on 3 February, he was giving the nurses cheek and, as usual, more concerned about my mother's welfare than his own." Early the following morning, however, he took a sudden turn for the worse and passed away in his sleep.

Vida Meares told me, "Marshall Grover and my husband were the same person -- and Horwitz killed Marshall Grover."

Though this was clearly not the case, I do believe that the decision taken by Horwitz to stop publishing Larry and Stretch, coupled with their refusal to allow him to take his pseudonym and characters elsewhere, certainly contributed to Len's decline.

The last two Leonard Meares books to appear in the BHW line -- Tin Star Trio (1994) and A Quest of Heroes (1996) -- were written not by Len at all, but by Link Hullar (himself the author of five BHWs) and me, from fragments found among Len's papers.

Tin Star Trio began life as an untitled short story featuring two drifters called Zack Holley and Curly Ryker. As soon as I started reading it, I realised that Len had been toying with the idea of continuing to write Larry and Stretch -- most probably for publication by Hale -- but changing the characters' names to avoid any legal difficulties. The story revolved around a missing cashbox hidden in a remote canyon, and told how Zack and Curly manage to thwart the attempts of a band of outlaws to retrieve it.

Link and I both felt that it would be a nice to expand the story into a short novel, and with the blessing of Vida Meares, that's exactly what we did. Although we aged the characters a little (because we've both always preferred westerns that feature older, slightly over-the-hill heroes), we tried to recapture some of the spirit of Len at his best. Even the titles of the chapters are all taken from previous Larry and Stretch books.

A Quest of Heroes came about at the suggestion of Australian singer Dave Mathewson, a Marshall Grover fan from way back, who had earlier recorded a sort of "tribute album" entitled The Marshall, Larry and Stretch and Me and You. Dave's brief plot, which was all about a bandit gang who kidnap white women in order to sell them into slavery south of the border, gave us an ideal opportunity to bring back not just Larry and Stretch (here once again masquerading as Zack and Curly), but all of Len's best-known characters, including Big Jim Rand, Slow Wolf, Dan Hoolihan and more. Naturally, we had to change the names of all the main players, but I like to think that we produced a book that Len would have approved of.

In any case, it's hardly my place to pass judgement on either Tin Star Trio or A Quest of Heroes, but I must say that I could not have wished for a better collaborator on these two projects. Link Hullar, like myself, was a close friend and fan of Len's, and I have always considered Link to be Len's natural successor.

Even though the BHWs of Len Meares might not be among his greatest achievements, I still enjoy re-reading them occasionally. Be they good, bad or indifferent, Len himself is there in every line, and reading them again is like visiting with him again. He was a skilled and tireless writer, a truly wonderful friend, and I remember him -- will always remember him -- with tremendous affection.

This article first appeared in the pages of Keith Chapman's Black Horse Extra. www.blackhorsewesterns.com

Len worked at a variety of jobs after leaving school, including shoe salesman, and during the Second World War he served with the Royal Australian Air Force. When he returned to civilian life in 1946, he went to work at Australia's Department of Immigration.

The aspiring author bought his first typewriter in the mid-1950s with the intention of writing for radio and the cinema, but when this proved to be easier said than done, he decided to try his hand at popular fiction instead. Since a great many paperback westerns were being published locally, he set about writing one of his own. The result, Trouble Town, was published by the Cleveland Publishing Company in 1955. Although Len had devised the pseudonym "Marshall Grover" for his first book, however, Cleveland decided to issue it under the name Johnny Nelson. "I'm still chagrined about that," he told me years later. Undaunted, he quickly developed a facility for writing westerns, and Cleveland eventually put him under contract. His tenth yarn, Drift!, (1956), introduced his fiddle-footed knights-errant, Larry Valentine and Stretch Emerson, the characters for which he would eventually become so beloved. And nowhere was the author's quirky sense of humor more apparent than in these action-packed and always painstakingly plotted yarns.

With his work appearing under such names as "Ward Brennan", "Glenn Murrell", "Shad Denver" and even "Brett Waring" (a pseudonym more correctly associated with Keith Hetherington), Len never needed more than 24 hours to devise a new plot. "Irving Berlin once said that there are so many notes on a keyboard from which to create a new melody, and it's the same with writing on a treadmill basis."

At his most prolific, the by-now full-time writer could turn out around thirty books a year. In 1960, he created a brief but memorable series of westerns set in and around the town of Bleak Creek. Four years later came The Night McLennan Died, the first of more than 70 oaters to feature cavalryman-turned-manhunter Big Jim Rand.

In mid-1966, Len left Cleveland and started writing exclusively for the Horwitz Group. Quick to exploit its latest asset, Horwitz soon sold more than 30 novels to Bantam Books for publication in the United States, where for legal reasons "Marshall Grover" became "Marshall McCoy", "Larry and Stretch" became "Larry and Streak" and "Big Jim Rand" became "Nevada Jim Gage". With their tighter editing and wonderful James Bama covers, I believe the westerns issued during this period are probably the author's best.

Although I started reading the Larry and Stretch series when I was about 10 years old, it wasn't until 1979 (and I had reached the ripe old age of 21) that I finally decided to contact the author, via his publisher. When he eventually replied, I discovered a genial, self-deprecating and incredibly genuine man who showed real interest in his readers. And since we seemed to hit it off so well, what started out as a simple, one-off letter of appreciation quickly blossomed into a warm and lively correspondence which was to last for 14 years.

Len began his association with Robert Hale Limited in 1981, with Jo Jo and the Private Eye, the first of five "Marty Moon" detective novels published under the name "Lester Malloy". Hale also issued his offbeat romance, The Future and Philomena, as by "Val Sterling", in 1982. He even scored with two stand-alone crime novels, The Battle of Jericho Street (1984) as by "Frank Everton", and Dead Man Smiling (1986), published under his own name.

His first Black Horse Western was, fittingly enough, a Larry and Stretch yarn entitled Rescue a Tall Texan (1989). It's an entertaining entry in the long-running series in which Stretch, the homely, amiable but always slower-witted half of the duo, is kidnapped by an outlaw gang in need of a hostage. Naturally, Larry quickly sets out to track down and rescue his partner, and is joined along the way by an erudite half-Sioux Indian with the unlikely name of Cathcart P. Slow Wolf, and the always-apoplectic Pinkerton operative, Dan Hoolihan, both popular recurring characters in the series. The climax is a typically robust shootout in which Larry and Stretch mix it up with no less than 13 hardcases -- 13, in this instance, proving to be an extremely unlucky number for the bad guys.

At Len's suggestion, the UK hardcover rights in Rescue a Tall Texan were sold to Hale by the Horwitz Group, and I've always wondered why Horwitz never tried to sell any further Larry and Stretch westerns on to the good folks at Clerkenwell House. Certainly, these books remain enormously popular with the library readership, and Ulverscroft continue to issue large print Linford editions, even today.

In any case, Len soon decided to create a new double-act specifically for the Black Horse Western market, in the shape of husband-and-wife detectives Rick and Hattie Braddock.

Rick and Hattie first appeared in Colorado Runaround, which was published in 1991. Rick is a former cowboy, actor and gambler, Hattie (nee Keever) a one-time magician's assistant, chorus girl and knife-thrower's target. Thrown together by circumstances, the couple eventually fall in love, get spliced and set up the Braddock Detective Agency. Their first case involves the disappearance of a wealthy rancher's daughter, and it takes place -- as did all of Len's westerns -- on an historically sketchy but always largely good-natured frontier, where the harsh realities of life seldom make an appearance.

And in that last respect, Len's fiction always reflected his own character, for here was a very moral and fair-minded man with a commendably innocent, straightforward and almost naive outlook on life -- a man who would always rather see the good in a person, place or situation than the bad.

Colorado Runaround, like the BHWs which followed it, is typical -- though not vintage -- Meares. There's a deceptively intricate plot, regular bursts of action, oddball supporting characters and plenty of laughs. In all respects, it is the work of a writer's writer. But the humour is somewhat hit-or-miss, and is as likely to make the story as break it.

This observation also applies to Len's three "Rick and Hattie" sequels, The Major and the Miners (1992), in which the heroes attempt to solve a whole passel of mysteries and restore peace to an increasingly restive mining town; Five Deadly Shadows (1993), a far more satisfying kidnap story; and Feud at Greco Canyon (1994), in which the happily married sleuths work overtime to avert a full-scale range-war.

Len's final western series, set in Rampart County, Montana, is probably his most disappointing. Montana Crisis (1993) is a pretty standard tale about how a growing town gets a sheriff -- in the form of overly officious ex-Pinkerton operative Francis X. Rooney -- and his laconic deputy, Memphis Beck. In the first adventure, they break the iron rule of megalomaniac entrepreneur Leon Coghill, but curiously, there's more talk than action.

Things perk up a bit in the sequel, Rooney's Second Deputy (1994), a mystery that also involves a daring robbery. This time round, the story is propelled more by gambler Beau Latimore (the deputy of the title) and Len's supporting characters, who prove to be far more "reader friendly" than the starchy Rooney.

In summary then, it is probably fairer to judge Len's undoubted merits as a western writer more on his Cleveland and Horwitz titles -- which I cannot praise highly enough -- than those he wrote for Hale. But why should this be?

To answer that question, we need to understand what was happening in Len's professional life at that time they were written.

In the spring of 1991, the author was requested by Horwitz not to produce any more Larry and Stretch westerns for six months. Apparently, Horwitz had built up a substantial backlog of material, and couldn't see much point in buying new manuscripts when there were so many older ones still awaiting publication. It was during this period that Len wrote and sold his first BHW.

When he delivered his next "Marshall Grover" book ahead of Christmas 1991, however, Horwitz dropped a bombshell. The company had decided to close down its paperback arm altogether, and in future would only require one Larry and Stretch story each month (as against the two Len usually produced), to sell on to the still-buoyant Scandinavian market.

Len's wife, Vida, put it this way: "He was more or less sacked."

Len's immediate instinct was to find another publisher and continue writing Marshall Grover westerns for the English-speaking market. Under the terms of his contract, however, Horwitz owned both the Grover name and the Grover characters -- and weren't about to allow him to take them anywhere else.

To a man who had spent 36 years as "the Marshall", and almost as long writing literally hundreds of Larry and Stretch yarns, it was a devastating turn of events -- not least financially -- and Len quickly went into decline. In a letter to me, Vida Meares remembered, "When out of our home or talking on the phone, [Len] was still the same cheerful, quick-witted man, but at home he was downhearted and feeling well-nigh finished."

And though he continued to write Larry and Stretch, he often told me how unhappy he was that his English-speaking fans, who had stuck with the series for so long, would no longer get the chance to follow the Texans' adventures.

This, then, was the backdrop against which Len wrote his Black Horse Westerns. In low spirits, and with his professional life in turmoil, I believe he was attempting to create new characters to replace those who had become his constant companions over the years, and whom he viewed very much as his "children". But though he gave each and every one of his BHWs as much care and attention as possible, Larry and Stretch proved to be an impossible act to follow -- which only depressed him more.

Just over a year later, in January 1993, Len contracted viral pneumonia and was hospitalised for the condition. His daughter Gaby later wrote to me, "When I visited him on 3 February, he was giving the nurses cheek and, as usual, more concerned about my mother's welfare than his own." Early the following morning, however, he took a sudden turn for the worse and passed away in his sleep.

Vida Meares told me, "Marshall Grover and my husband were the same person -- and Horwitz killed Marshall Grover."

Though this was clearly not the case, I do believe that the decision taken by Horwitz to stop publishing Larry and Stretch, coupled with their refusal to allow him to take his pseudonym and characters elsewhere, certainly contributed to Len's decline.

The last two Leonard Meares books to appear in the BHW line -- Tin Star Trio (1994) and A Quest of Heroes (1996) -- were written not by Len at all, but by Link Hullar (himself the author of five BHWs) and me, from fragments found among Len's papers.

Tin Star Trio began life as an untitled short story featuring two drifters called Zack Holley and Curly Ryker. As soon as I started reading it, I realised that Len had been toying with the idea of continuing to write Larry and Stretch -- most probably for publication by Hale -- but changing the characters' names to avoid any legal difficulties. The story revolved around a missing cashbox hidden in a remote canyon, and told how Zack and Curly manage to thwart the attempts of a band of outlaws to retrieve it.

Link and I both felt that it would be a nice to expand the story into a short novel, and with the blessing of Vida Meares, that's exactly what we did. Although we aged the characters a little (because we've both always preferred westerns that feature older, slightly over-the-hill heroes), we tried to recapture some of the spirit of Len at his best. Even the titles of the chapters are all taken from previous Larry and Stretch books.

A Quest of Heroes came about at the suggestion of Australian singer Dave Mathewson, a Marshall Grover fan from way back, who had earlier recorded a sort of "tribute album" entitled The Marshall, Larry and Stretch and Me and You. Dave's brief plot, which was all about a bandit gang who kidnap white women in order to sell them into slavery south of the border, gave us an ideal opportunity to bring back not just Larry and Stretch (here once again masquerading as Zack and Curly), but all of Len's best-known characters, including Big Jim Rand, Slow Wolf, Dan Hoolihan and more. Naturally, we had to change the names of all the main players, but I like to think that we produced a book that Len would have approved of.

In any case, it's hardly my place to pass judgement on either Tin Star Trio or A Quest of Heroes, but I must say that I could not have wished for a better collaborator on these two projects. Link Hullar, like myself, was a close friend and fan of Len's, and I have always considered Link to be Len's natural successor.

Even though the BHWs of Len Meares might not be among his greatest achievements, I still enjoy re-reading them occasionally. Be they good, bad or indifferent, Len himself is there in every line, and reading them again is like visiting with him again. He was a skilled and tireless writer, a truly wonderful friend, and I remember him -- will always remember him -- with tremendous affection.

This article first appeared in the pages of Keith Chapman's Black Horse Extra. www.blackhorsewesterns.com

The aspiring author bought his first typewriter in the mid-1950s with the intention of writing for radio and the cinema, but when this proved to be easier said than done, he decided to try his hand at popular fiction instead. Since a great many paperback westerns were being published locally, he set about writing one of his own. The result, Trouble Town, was published by the Cleveland Publishing Company in 1955. Although Len had devised the pseudonym "Marshall Grover" for his first book, however, Cleveland decided to issue it under the name Johnny Nelson. "I'm still chagrined about that," he told me years later. Undaunted, he quickly developed a facility for writing westerns, and Cleveland eventually put him under contract. His tenth yarn, Drift!, (1956), introduced his fiddle-footed knights-errant, Larry Valentine and Stretch Emerson, the characters for which he would eventually become so beloved. And nowhere was the author's quirky sense of humor more apparent than in these action-packed and always painstakingly plotted yarns.

With his work appearing under such names as "Ward Brennan", "Glenn Murrell", "Shad Denver" and even "Brett Waring" (a pseudonym more correctly associated with Keith Hetherington), Len never needed more than 24 hours to devise a new plot. "Irving Berlin once said that there are so many notes on a keyboard from which to create a new melody, and it's the same with writing on a treadmill basis."

At his most prolific, the by-now full-time writer could turn out around thirty books a year. In 1960, he created a brief but memorable series of westerns set in and around the town of Bleak Creek. Four years later came The Night McLennan Died, the first of more than 70 oaters to feature cavalryman-turned-manhunter Big Jim Rand.

In mid-1966, Len left Cleveland and started writing exclusively for the Horwitz Group. Quick to exploit its latest asset, Horwitz soon sold more than 30 novels to Bantam Books for publication in the United States, where for legal reasons "Marshall Grover" became "Marshall McCoy", "Larry and Stretch" became "Larry and Streak" and "Big Jim Rand" became "Nevada Jim Gage". With their tighter editing and wonderful James Bama covers, I believe the westerns issued during this period are probably the author's best.

Although I started reading the Larry and Stretch series when I was about 10 years old, it wasn't until 1979 (and I had reached the ripe old age of 21) that I finally decided to contact the author, via his publisher. When he eventually replied, I discovered a genial, self-deprecating and incredibly genuine man who showed real interest in his readers. And since we seemed to hit it off so well, what started out as a simple, one-off letter of appreciation quickly blossomed into a warm and lively correspondence which was to last for 14 years.

Len began his association with Robert Hale Limited in 1981, with Jo Jo and the Private Eye, the first of five "Marty Moon" detective novels published under the name "Lester Malloy". Hale also issued his offbeat romance, The Future and Philomena, as by "Val Sterling", in 1982. He even scored with two stand-alone crime novels, The Battle of Jericho Street (1984) as by "Frank Everton", and Dead Man Smiling (1986), published under his own name.

His first Black Horse Western was, fittingly enough, a Larry and Stretch yarn entitled Rescue a Tall Texan (1989). It's an entertaining entry in the long-running series in which Stretch, the homely, amiable but always slower-witted half of the duo, is kidnapped by an outlaw gang in need of a hostage. Naturally, Larry quickly sets out to track down and rescue his partner, and is joined along the way by an erudite half-Sioux Indian with the unlikely name of Cathcart P. Slow Wolf, and the always-apoplectic Pinkerton operative, Dan Hoolihan, both popular recurring characters in the series. The climax is a typically robust shootout in which Larry and Stretch mix it up with no less than 13 hardcases -- 13, in this instance, proving to be an extremely unlucky number for the bad guys.

At Len's suggestion, the UK hardcover rights in Rescue a Tall Texan were sold to Hale by the Horwitz Group, and I've always wondered why Horwitz never tried to sell any further Larry and Stretch westerns on to the good folks at Clerkenwell House. Certainly, these books remain enormously popular with the library readership, and Ulverscroft continue to issue large print Linford editions, even today.

In any case, Len soon decided to create a new double-act specifically for the Black Horse Western market, in the shape of husband-and-wife detectives Rick and Hattie Braddock.

Rick and Hattie first appeared in Colorado Runaround, which was published in 1991. Rick is a former cowboy, actor and gambler, Hattie (nee Keever) a one-time magician's assistant, chorus girl and knife-thrower's target. Thrown together by circumstances, the couple eventually fall in love, get spliced and set up the Braddock Detective Agency. Their first case involves the disappearance of a wealthy rancher's daughter, and it takes place -- as did all of Len's westerns -- on an historically sketchy but always largely good-natured frontier, where the harsh realities of life seldom make an appearance.

And in that last respect, Len's fiction always reflected his own character, for here was a very moral and fair-minded man with a commendably innocent, straightforward and almost naive outlook on life -- a man who would always rather see the good in a person, place or situation than the bad.

Colorado Runaround, like the BHWs which followed it, is typical -- though not vintage -- Meares. There's a deceptively intricate plot, regular bursts of action, oddball supporting characters and plenty of laughs. In all respects, it is the work of a writer's writer. But the humour is somewhat hit-or-miss, and is as likely to make the story as break it.

This observation also applies to Len's three "Rick and Hattie" sequels, The Major and the Miners (1992), in which the heroes attempt to solve a whole passel of mysteries and restore peace to an increasingly restive mining town; Five Deadly Shadows (1993), a far more satisfying kidnap story; and Feud at Greco Canyon (1994), in which the happily married sleuths work overtime to avert a full-scale range-war.

Len's final western series, set in Rampart County, Montana, is probably his most disappointing. Montana Crisis (1993) is a pretty standard tale about how a growing town gets a sheriff -- in the form of overly officious ex-Pinkerton operative Francis X. Rooney -- and his laconic deputy, Memphis Beck. In the first adventure, they break the iron rule of megalomaniac entrepreneur Leon Coghill, but curiously, there's more talk than action.

Things perk up a bit in the sequel, Rooney's Second Deputy (1994), a mystery that also involves a daring robbery. This time round, the story is propelled more by gambler Beau Latimore (the deputy of the title) and Len's supporting characters, who prove to be far more "reader friendly" than the starchy Rooney.

In summary then, it is probably fairer to judge Len's undoubted merits as a western writer more on his Cleveland and Horwitz titles -- which I cannot praise highly enough -- than those he wrote for Hale. But why should this be?

To answer that question, we need to understand what was happening in Len's professional life at that time they were written.

In the spring of 1991, the author was requested by Horwitz not to produce any more Larry and Stretch westerns for six months. Apparently, Horwitz had built up a substantial backlog of material, and couldn't see much point in buying new manuscripts when there were so many older ones still awaiting publication. It was during this period that Len wrote and sold his first BHW.

When he delivered his next "Marshall Grover" book ahead of Christmas 1991, however, Horwitz dropped a bombshell. The company had decided to close down its paperback arm altogether, and in future would only require one Larry and Stretch story each month (as against the two Len usually produced), to sell on to the still-buoyant Scandinavian market.

Len's wife, Vida, put it this way: "He was more or less sacked."

Len's immediate instinct was to find another publisher and continue writing Marshall Grover westerns for the English-speaking market. Under the terms of his contract, however, Horwitz owned both the Grover name and the Grover characters -- and weren't about to allow him to take them anywhere else.

To a man who had spent 36 years as "the Marshall", and almost as long writing literally hundreds of Larry and Stretch yarns, it was a devastating turn of events -- not least financially -- and Len quickly went into decline. In a letter to me, Vida Meares remembered, "When out of our home or talking on the phone, [Len] was still the same cheerful, quick-witted man, but at home he was downhearted and feeling well-nigh finished."

And though he continued to write Larry and Stretch, he often told me how unhappy he was that his English-speaking fans, who had stuck with the series for so long, would no longer get the chance to follow the Texans' adventures.

This, then, was the backdrop against which Len wrote his Black Horse Westerns. In low spirits, and with his professional life in turmoil, I believe he was attempting to create new characters to replace those who had become his constant companions over the years, and whom he viewed very much as his "children". But though he gave each and every one of his BHWs as much care and attention as possible, Larry and Stretch proved to be an impossible act to follow -- which only depressed him more.

Just over a year later, in January 1993, Len contracted viral pneumonia and was hospitalised for the condition. His daughter Gaby later wrote to me, "When I visited him on 3 February, he was giving the nurses cheek and, as usual, more concerned about my mother's welfare than his own." Early the following morning, however, he took a sudden turn for the worse and passed away in his sleep.

Vida Meares told me, "Marshall Grover and my husband were the same person -- and Horwitz killed Marshall Grover."

Though this was clearly not the case, I do believe that the decision taken by Horwitz to stop publishing Larry and Stretch, coupled with their refusal to allow him to take his pseudonym and characters elsewhere, certainly contributed to Len's decline.

The last two Leonard Meares books to appear in the BHW line -- Tin Star Trio (1994) and A Quest of Heroes (1996) -- were written not by Len at all, but by Link Hullar (himself the author of five BHWs) and me, from fragments found among Len's papers.

Tin Star Trio began life as an untitled short story featuring two drifters called Zack Holley and Curly Ryker. As soon as I started reading it, I realised that Len had been toying with the idea of continuing to write Larry and Stretch -- most probably for publication by Hale -- but changing the characters' names to avoid any legal difficulties. The story revolved around a missing cashbox hidden in a remote canyon, and told how Zack and Curly manage to thwart the attempts of a band of outlaws to retrieve it.

Link and I both felt that it would be a nice to expand the story into a short novel, and with the blessing of Vida Meares, that's exactly what we did. Although we aged the characters a little (because we've both always preferred westerns that feature older, slightly over-the-hill heroes), we tried to recapture some of the spirit of Len at his best. Even the titles of the chapters are all taken from previous Larry and Stretch books.

A Quest of Heroes came about at the suggestion of Australian singer Dave Mathewson, a Marshall Grover fan from way back, who had earlier recorded a sort of "tribute album" entitled The Marshall, Larry and Stretch and Me and You. Dave's brief plot, which was all about a bandit gang who kidnap white women in order to sell them into slavery south of the border, gave us an ideal opportunity to bring back not just Larry and Stretch (here once again masquerading as Zack and Curly), but all of Len's best-known characters, including Big Jim Rand, Slow Wolf, Dan Hoolihan and more. Naturally, we had to change the names of all the main players, but I like to think that we produced a book that Len would have approved of.

In any case, it's hardly my place to pass judgement on either Tin Star Trio or A Quest of Heroes, but I must say that I could not have wished for a better collaborator on these two projects. Link Hullar, like myself, was a close friend and fan of Len's, and I have always considered Link to be Len's natural successor.

Even though the BHWs of Len Meares might not be among his greatest achievements, I still enjoy re-reading them occasionally. Be they good, bad or indifferent, Len himself is there in every line, and reading them again is like visiting with him again. He was a skilled and tireless writer, a truly wonderful friend, and I remember him -- will always remember him -- with tremendous affection.

This article first appeared in the pages of Keith Chapman's Black Horse Extra. www.blackhorsewesterns.com

With his work appearing under such names as "Ward Brennan", "Glenn Murrell", "Shad Denver" and even "Brett Waring" (a pseudonym more correctly associated with Keith Hetherington), Len never needed more than 24 hours to devise a new plot. "Irving Berlin once said that there are so many notes on a keyboard from which to create a new melody, and it's the same with writing on a treadmill basis."

At his most prolific, the by-now full-time writer could turn out around thirty books a year. In 1960, he created a brief but memorable series of westerns set in and around the town of Bleak Creek. Four years later came The Night McLennan Died, the first of more than 70 oaters to feature cavalryman-turned-manhunter Big Jim Rand.

In mid-1966, Len left Cleveland and started writing exclusively for the Horwitz Group. Quick to exploit its latest asset, Horwitz soon sold more than 30 novels to Bantam Books for publication in the United States, where for legal reasons "Marshall Grover" became "Marshall McCoy", "Larry and Stretch" became "Larry and Streak" and "Big Jim Rand" became "Nevada Jim Gage". With their tighter editing and wonderful James Bama covers, I believe the westerns issued during this period are probably the author's best.

Although I started reading the Larry and Stretch series when I was about 10 years old, it wasn't until 1979 (and I had reached the ripe old age of 21) that I finally decided to contact the author, via his publisher. When he eventually replied, I discovered a genial, self-deprecating and incredibly genuine man who showed real interest in his readers. And since we seemed to hit it off so well, what started out as a simple, one-off letter of appreciation quickly blossomed into a warm and lively correspondence which was to last for 14 years.

Len began his association with Robert Hale Limited in 1981, with Jo Jo and the Private Eye, the first of five "Marty Moon" detective novels published under the name "Lester Malloy". Hale also issued his offbeat romance, The Future and Philomena, as by "Val Sterling", in 1982. He even scored with two stand-alone crime novels, The Battle of Jericho Street (1984) as by "Frank Everton", and Dead Man Smiling (1986), published under his own name.

His first Black Horse Western was, fittingly enough, a Larry and Stretch yarn entitled Rescue a Tall Texan (1989). It's an entertaining entry in the long-running series in which Stretch, the homely, amiable but always slower-witted half of the duo, is kidnapped by an outlaw gang in need of a hostage. Naturally, Larry quickly sets out to track down and rescue his partner, and is joined along the way by an erudite half-Sioux Indian with the unlikely name of Cathcart P. Slow Wolf, and the always-apoplectic Pinkerton operative, Dan Hoolihan, both popular recurring characters in the series. The climax is a typically robust shootout in which Larry and Stretch mix it up with no less than 13 hardcases -- 13, in this instance, proving to be an extremely unlucky number for the bad guys.

At Len's suggestion, the UK hardcover rights in Rescue a Tall Texan were sold to Hale by the Horwitz Group, and I've always wondered why Horwitz never tried to sell any further Larry and Stretch westerns on to the good folks at Clerkenwell House. Certainly, these books remain enormously popular with the library readership, and Ulverscroft continue to issue large print Linford editions, even today.

In any case, Len soon decided to create a new double-act specifically for the Black Horse Western market, in the shape of husband-and-wife detectives Rick and Hattie Braddock.

Rick and Hattie first appeared in Colorado Runaround, which was published in 1991. Rick is a former cowboy, actor and gambler, Hattie (nee Keever) a one-time magician's assistant, chorus girl and knife-thrower's target. Thrown together by circumstances, the couple eventually fall in love, get spliced and set up the Braddock Detective Agency. Their first case involves the disappearance of a wealthy rancher's daughter, and it takes place -- as did all of Len's westerns -- on an historically sketchy but always largely good-natured frontier, where the harsh realities of life seldom make an appearance.

And in that last respect, Len's fiction always reflected his own character, for here was a very moral and fair-minded man with a commendably innocent, straightforward and almost naive outlook on life -- a man who would always rather see the good in a person, place or situation than the bad.

Colorado Runaround, like the BHWs which followed it, is typical -- though not vintage -- Meares. There's a deceptively intricate plot, regular bursts of action, oddball supporting characters and plenty of laughs. In all respects, it is the work of a writer's writer. But the humour is somewhat hit-or-miss, and is as likely to make the story as break it.

This observation also applies to Len's three "Rick and Hattie" sequels, The Major and the Miners (1992), in which the heroes attempt to solve a whole passel of mysteries and restore peace to an increasingly restive mining town; Five Deadly Shadows (1993), a far more satisfying kidnap story; and Feud at Greco Canyon (1994), in which the happily married sleuths work overtime to avert a full-scale range-war.

Len's final western series, set in Rampart County, Montana, is probably his most disappointing. Montana Crisis (1993) is a pretty standard tale about how a growing town gets a sheriff -- in the form of overly officious ex-Pinkerton operative Francis X. Rooney -- and his laconic deputy, Memphis Beck. In the first adventure, they break the iron rule of megalomaniac entrepreneur Leon Coghill, but curiously, there's more talk than action.

Things perk up a bit in the sequel, Rooney's Second Deputy (1994), a mystery that also involves a daring robbery. This time round, the story is propelled more by gambler Beau Latimore (the deputy of the title) and Len's supporting characters, who prove to be far more "reader friendly" than the starchy Rooney.

In summary then, it is probably fairer to judge Len's undoubted merits as a western writer more on his Cleveland and Horwitz titles -- which I cannot praise highly enough -- than those he wrote for Hale. But why should this be?

To answer that question, we need to understand what was happening in Len's professional life at that time they were written.

In the spring of 1991, the author was requested by Horwitz not to produce any more Larry and Stretch westerns for six months. Apparently, Horwitz had built up a substantial backlog of material, and couldn't see much point in buying new manuscripts when there were so many older ones still awaiting publication. It was during this period that Len wrote and sold his first BHW.

When he delivered his next "Marshall Grover" book ahead of Christmas 1991, however, Horwitz dropped a bombshell. The company had decided to close down its paperback arm altogether, and in future would only require one Larry and Stretch story each month (as against the two Len usually produced), to sell on to the still-buoyant Scandinavian market.

Len's wife, Vida, put it this way: "He was more or less sacked."

Len's immediate instinct was to find another publisher and continue writing Marshall Grover westerns for the English-speaking market. Under the terms of his contract, however, Horwitz owned both the Grover name and the Grover characters -- and weren't about to allow him to take them anywhere else.

To a man who had spent 36 years as "the Marshall", and almost as long writing literally hundreds of Larry and Stretch yarns, it was a devastating turn of events -- not least financially -- and Len quickly went into decline. In a letter to me, Vida Meares remembered, "When out of our home or talking on the phone, [Len] was still the same cheerful, quick-witted man, but at home he was downhearted and feeling well-nigh finished."

And though he continued to write Larry and Stretch, he often told me how unhappy he was that his English-speaking fans, who had stuck with the series for so long, would no longer get the chance to follow the Texans' adventures.

This, then, was the backdrop against which Len wrote his Black Horse Westerns. In low spirits, and with his professional life in turmoil, I believe he was attempting to create new characters to replace those who had become his constant companions over the years, and whom he viewed very much as his "children". But though he gave each and every one of his BHWs as much care and attention as possible, Larry and Stretch proved to be an impossible act to follow -- which only depressed him more.

Just over a year later, in January 1993, Len contracted viral pneumonia and was hospitalised for the condition. His daughter Gaby later wrote to me, "When I visited him on 3 February, he was giving the nurses cheek and, as usual, more concerned about my mother's welfare than his own." Early the following morning, however, he took a sudden turn for the worse and passed away in his sleep.

Vida Meares told me, "Marshall Grover and my husband were the same person -- and Horwitz killed Marshall Grover."

Though this was clearly not the case, I do believe that the decision taken by Horwitz to stop publishing Larry and Stretch, coupled with their refusal to allow him to take his pseudonym and characters elsewhere, certainly contributed to Len's decline.

The last two Leonard Meares books to appear in the BHW line -- Tin Star Trio (1994) and A Quest of Heroes (1996) -- were written not by Len at all, but by Link Hullar (himself the author of five BHWs) and me, from fragments found among Len's papers.

Tin Star Trio began life as an untitled short story featuring two drifters called Zack Holley and Curly Ryker. As soon as I started reading it, I realised that Len had been toying with the idea of continuing to write Larry and Stretch -- most probably for publication by Hale -- but changing the characters' names to avoid any legal difficulties. The story revolved around a missing cashbox hidden in a remote canyon, and told how Zack and Curly manage to thwart the attempts of a band of outlaws to retrieve it.

Link and I both felt that it would be a nice to expand the story into a short novel, and with the blessing of Vida Meares, that's exactly what we did. Although we aged the characters a little (because we've both always preferred westerns that feature older, slightly over-the-hill heroes), we tried to recapture some of the spirit of Len at his best. Even the titles of the chapters are all taken from previous Larry and Stretch books.

A Quest of Heroes came about at the suggestion of Australian singer Dave Mathewson, a Marshall Grover fan from way back, who had earlier recorded a sort of "tribute album" entitled The Marshall, Larry and Stretch and Me and You. Dave's brief plot, which was all about a bandit gang who kidnap white women in order to sell them into slavery south of the border, gave us an ideal opportunity to bring back not just Larry and Stretch (here once again masquerading as Zack and Curly), but all of Len's best-known characters, including Big Jim Rand, Slow Wolf, Dan Hoolihan and more. Naturally, we had to change the names of all the main players, but I like to think that we produced a book that Len would have approved of.

In any case, it's hardly my place to pass judgement on either Tin Star Trio or A Quest of Heroes, but I must say that I could not have wished for a better collaborator on these two projects. Link Hullar, like myself, was a close friend and fan of Len's, and I have always considered Link to be Len's natural successor.

Even though the BHWs of Len Meares might not be among his greatest achievements, I still enjoy re-reading them occasionally. Be they good, bad or indifferent, Len himself is there in every line, and reading them again is like visiting with him again. He was a skilled and tireless writer, a truly wonderful friend, and I remember him -- will always remember him -- with tremendous affection.

This article first appeared in the pages of Keith Chapman's Black Horse Extra. www.blackhorsewesterns.com

At his most prolific, the by-now full-time writer could turn out around thirty books a year. In 1960, he created a brief but memorable series of westerns set in and around the town of Bleak Creek. Four years later came The Night McLennan Died, the first of more than 70 oaters to feature cavalryman-turned-manhunter Big Jim Rand.

In mid-1966, Len left Cleveland and started writing exclusively for the Horwitz Group. Quick to exploit its latest asset, Horwitz soon sold more than 30 novels to Bantam Books for publication in the United States, where for legal reasons "Marshall Grover" became "Marshall McCoy", "Larry and Stretch" became "Larry and Streak" and "Big Jim Rand" became "Nevada Jim Gage". With their tighter editing and wonderful James Bama covers, I believe the westerns issued during this period are probably the author's best.

Although I started reading the Larry and Stretch series when I was about 10 years old, it wasn't until 1979 (and I had reached the ripe old age of 21) that I finally decided to contact the author, via his publisher. When he eventually replied, I discovered a genial, self-deprecating and incredibly genuine man who showed real interest in his readers. And since we seemed to hit it off so well, what started out as a simple, one-off letter of appreciation quickly blossomed into a warm and lively correspondence which was to last for 14 years.

Len began his association with Robert Hale Limited in 1981, with Jo Jo and the Private Eye, the first of five "Marty Moon" detective novels published under the name "Lester Malloy". Hale also issued his offbeat romance, The Future and Philomena, as by "Val Sterling", in 1982. He even scored with two stand-alone crime novels, The Battle of Jericho Street (1984) as by "Frank Everton", and Dead Man Smiling (1986), published under his own name.

His first Black Horse Western was, fittingly enough, a Larry and Stretch yarn entitled Rescue a Tall Texan (1989). It's an entertaining entry in the long-running series in which Stretch, the homely, amiable but always slower-witted half of the duo, is kidnapped by an outlaw gang in need of a hostage. Naturally, Larry quickly sets out to track down and rescue his partner, and is joined along the way by an erudite half-Sioux Indian with the unlikely name of Cathcart P. Slow Wolf, and the always-apoplectic Pinkerton operative, Dan Hoolihan, both popular recurring characters in the series. The climax is a typically robust shootout in which Larry and Stretch mix it up with no less than 13 hardcases -- 13, in this instance, proving to be an extremely unlucky number for the bad guys.

At Len's suggestion, the UK hardcover rights in Rescue a Tall Texan were sold to Hale by the Horwitz Group, and I've always wondered why Horwitz never tried to sell any further Larry and Stretch westerns on to the good folks at Clerkenwell House. Certainly, these books remain enormously popular with the library readership, and Ulverscroft continue to issue large print Linford editions, even today.

In any case, Len soon decided to create a new double-act specifically for the Black Horse Western market, in the shape of husband-and-wife detectives Rick and Hattie Braddock.

Rick and Hattie first appeared in Colorado Runaround, which was published in 1991. Rick is a former cowboy, actor and gambler, Hattie (nee Keever) a one-time magician's assistant, chorus girl and knife-thrower's target. Thrown together by circumstances, the couple eventually fall in love, get spliced and set up the Braddock Detective Agency. Their first case involves the disappearance of a wealthy rancher's daughter, and it takes place -- as did all of Len's westerns -- on an historically sketchy but always largely good-natured frontier, where the harsh realities of life seldom make an appearance.

And in that last respect, Len's fiction always reflected his own character, for here was a very moral and fair-minded man with a commendably innocent, straightforward and almost naive outlook on life -- a man who would always rather see the good in a person, place or situation than the bad.

Colorado Runaround, like the BHWs which followed it, is typical -- though not vintage -- Meares. There's a deceptively intricate plot, regular bursts of action, oddball supporting characters and plenty of laughs. In all respects, it is the work of a writer's writer. But the humour is somewhat hit-or-miss, and is as likely to make the story as break it.

This observation also applies to Len's three "Rick and Hattie" sequels, The Major and the Miners (1992), in which the heroes attempt to solve a whole passel of mysteries and restore peace to an increasingly restive mining town; Five Deadly Shadows (1993), a far more satisfying kidnap story; and Feud at Greco Canyon (1994), in which the happily married sleuths work overtime to avert a full-scale range-war.

Len's final western series, set in Rampart County, Montana, is probably his most disappointing. Montana Crisis (1993) is a pretty standard tale about how a growing town gets a sheriff -- in the form of overly officious ex-Pinkerton operative Francis X. Rooney -- and his laconic deputy, Memphis Beck. In the first adventure, they break the iron rule of megalomaniac entrepreneur Leon Coghill, but curiously, there's more talk than action.

Things perk up a bit in the sequel, Rooney's Second Deputy (1994), a mystery that also involves a daring robbery. This time round, the story is propelled more by gambler Beau Latimore (the deputy of the title) and Len's supporting characters, who prove to be far more "reader friendly" than the starchy Rooney.

In summary then, it is probably fairer to judge Len's undoubted merits as a western writer more on his Cleveland and Horwitz titles -- which I cannot praise highly enough -- than those he wrote for Hale. But why should this be?

To answer that question, we need to understand what was happening in Len's professional life at that time they were written.

In the spring of 1991, the author was requested by Horwitz not to produce any more Larry and Stretch westerns for six months. Apparently, Horwitz had built up a substantial backlog of material, and couldn't see much point in buying new manuscripts when there were so many older ones still awaiting publication. It was during this period that Len wrote and sold his first BHW.

When he delivered his next "Marshall Grover" book ahead of Christmas 1991, however, Horwitz dropped a bombshell. The company had decided to close down its paperback arm altogether, and in future would only require one Larry and Stretch story each month (as against the two Len usually produced), to sell on to the still-buoyant Scandinavian market.

Len's wife, Vida, put it this way: "He was more or less sacked."

Len's immediate instinct was to find another publisher and continue writing Marshall Grover westerns for the English-speaking market. Under the terms of his contract, however, Horwitz owned both the Grover name and the Grover characters -- and weren't about to allow him to take them anywhere else.

To a man who had spent 36 years as "the Marshall", and almost as long writing literally hundreds of Larry and Stretch yarns, it was a devastating turn of events -- not least financially -- and Len quickly went into decline. In a letter to me, Vida Meares remembered, "When out of our home or talking on the phone, [Len] was still the same cheerful, quick-witted man, but at home he was downhearted and feeling well-nigh finished."

And though he continued to write Larry and Stretch, he often told me how unhappy he was that his English-speaking fans, who had stuck with the series for so long, would no longer get the chance to follow the Texans' adventures.

This, then, was the backdrop against which Len wrote his Black Horse Westerns. In low spirits, and with his professional life in turmoil, I believe he was attempting to create new characters to replace those who had become his constant companions over the years, and whom he viewed very much as his "children". But though he gave each and every one of his BHWs as much care and attention as possible, Larry and Stretch proved to be an impossible act to follow -- which only depressed him more.

Just over a year later, in January 1993, Len contracted viral pneumonia and was hospitalised for the condition. His daughter Gaby later wrote to me, "When I visited him on 3 February, he was giving the nurses cheek and, as usual, more concerned about my mother's welfare than his own." Early the following morning, however, he took a sudden turn for the worse and passed away in his sleep.

Vida Meares told me, "Marshall Grover and my husband were the same person -- and Horwitz killed Marshall Grover."

Though this was clearly not the case, I do believe that the decision taken by Horwitz to stop publishing Larry and Stretch, coupled with their refusal to allow him to take his pseudonym and characters elsewhere, certainly contributed to Len's decline.

The last two Leonard Meares books to appear in the BHW line -- Tin Star Trio (1994) and A Quest of Heroes (1996) -- were written not by Len at all, but by Link Hullar (himself the author of five BHWs) and me, from fragments found among Len's papers.

Tin Star Trio began life as an untitled short story featuring two drifters called Zack Holley and Curly Ryker. As soon as I started reading it, I realised that Len had been toying with the idea of continuing to write Larry and Stretch -- most probably for publication by Hale -- but changing the characters' names to avoid any legal difficulties. The story revolved around a missing cashbox hidden in a remote canyon, and told how Zack and Curly manage to thwart the attempts of a band of outlaws to retrieve it.

Link and I both felt that it would be a nice to expand the story into a short novel, and with the blessing of Vida Meares, that's exactly what we did. Although we aged the characters a little (because we've both always preferred westerns that feature older, slightly over-the-hill heroes), we tried to recapture some of the spirit of Len at his best. Even the titles of the chapters are all taken from previous Larry and Stretch books.

A Quest of Heroes came about at the suggestion of Australian singer Dave Mathewson, a Marshall Grover fan from way back, who had earlier recorded a sort of "tribute album" entitled The Marshall, Larry and Stretch and Me and You. Dave's brief plot, which was all about a bandit gang who kidnap white women in order to sell them into slavery south of the border, gave us an ideal opportunity to bring back not just Larry and Stretch (here once again masquerading as Zack and Curly), but all of Len's best-known characters, including Big Jim Rand, Slow Wolf, Dan Hoolihan and more. Naturally, we had to change the names of all the main players, but I like to think that we produced a book that Len would have approved of.

In any case, it's hardly my place to pass judgement on either Tin Star Trio or A Quest of Heroes, but I must say that I could not have wished for a better collaborator on these two projects. Link Hullar, like myself, was a close friend and fan of Len's, and I have always considered Link to be Len's natural successor.

Even though the BHWs of Len Meares might not be among his greatest achievements, I still enjoy re-reading them occasionally. Be they good, bad or indifferent, Len himself is there in every line, and reading them again is like visiting with him again. He was a skilled and tireless writer, a truly wonderful friend, and I remember him -- will always remember him -- with tremendous affection.

This article first appeared in the pages of Keith Chapman's Black Horse Extra. www.blackhorsewesterns.com